The PIARA Project

PIARA is a regionally-focused and collaborative archaeological project that grew out of the research objectives and dissertation work of principal investigator Rebecca Bria (University of Minnesota–Twin Cities; Ph.D. Vanderbilt University). The overarching goal of the research is to understand longterm shifts in social and political organization in highland Ancash, Peru by examining transformations in ritual, economy, and ecology. Since 2009, this work has been carried out in collaboration with Peruvian archaeologists and PIARA co-directors Elizabeth Cruzado, Felipe Livora, and Cora Rivas as well as with several material specialists and student collaborators.

Investigating Hualcayán and Pariamarca

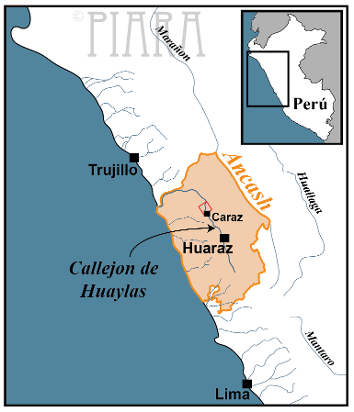

Centered on the Province of Huaylas, PIARA began its investigations with a regional survey in the northern Callejón de Huaylas valley in 2007 and 2009, which revealed dense occupations dating between the Late Preceramic Period and the Early Colonial Period (~2500 BC to ~AD 1600).

To begin unravelling this sequence of prehistoric developments, we conducted test excavations in 2009 at two large, multi-component archaeological complexes, Hualcayán and Pariamarca. We selected Hualcayán and Pariamarca for further study due to the material evidence that each had served as a ceremonial and habitation center for thousands of years. By investigating these long-occupied, multi-component sites, we were able to address questions concerning how these places—and the ancient communities that built them—maintained significance for millennia even as they were reassembled, or made anew, when local people innovated ritual, economic, and domestic practices or introduced new materials through time.

Investigations at Pariamarca revealed evidence that the site was both a Recuay ceremonial fortress (AD 1–700) and a pre-Inka and Inka civic-ceremonial center (AD 1000–1532), as well as that these complexes may have been constructed atop even earlier mound structures. Excavations at Hualcayán uncovered evidence that a ceremonial mound and plaza complex was built and reused for three thousand years during the Mito-Kotosh, Chavín, Huarás, and Recuay cultural phases (2400 BC–AD 700), and intensive mapping and surface collection beyond the mound revealed that Recuay and late Pre-Inka groups built extensive mortuary, domestic, and agricultural structures at the site (AD 1–1450).

The Study at Hualcayán

Despite exceptional findings at both sites, since 2010 we have focused our investigations at Hualcayán due to the evidence we uncovered for an ongoing, uninterrupted sequence of community activities across nearly all of Peru's major prehistoric periods at the site. In particular, Hualcayán provided an exceptional opportunity to explore the long-term, local processes of community formation in ancient highland Ancash. Though the entire sequence was of interest, attention was given to understanding one of the most transformative but little understood periods in Andean prehistory: Chavín to Recuay transition. This transition involved the disintegration of the widespread Chavín religious and political network (900–500 BC) and the subsequent emergence of more localized Recuay communities and polities across highland Ancash (AD 1–700). We were also interested in understanding the unique way that Hualcayán's ancient inhabitants seemingly integrated agricultural features (i.e. terraces and canals) with ritual spaces (i.e. ceremonial compounds and plazas) as they rebuilt their community during this transition. These observations led to questions concerning how ritual and economic practices interlink to organize societies and shape local ecologies. The PIARA project plans to return to investigate Pariamarca in the future, but it has committed to studying Hualcayán's complex history for a number of years as a way to robustly address these questions of ritual ecology in the ancient world.

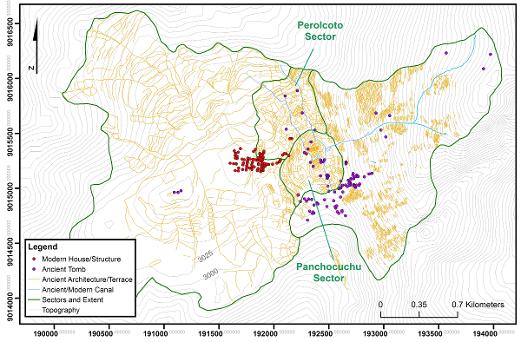

Between 2009 and 2013, our excavations uncovered 569 m2 of ancient remains at Hualcayán. Many of these excavations were focused on the ceremonial mounds, plazas, compounds, and terraces in the Perolcoto sector, where we documented changes in building, performance, food production, and ritual consumption across the Mito-Kotosh, Chavín, Huarás, and Recuay cultural phases (2400 BC - AD 700). Architectural, ceramic, botanical, faunal, and lithic remains revealed many complex shifts in community organization in practice through time. Notably, the evidence suggests that as local people developed Recuay cultural practices, such as feasting to venerate ancestors, they also intensified and diversified their food production practices. The data also suggest that they decentralized community ritual and labor activities during this transition by forming corporate groups, likely lineages, that held exclusive feasts, buried their dead, and stored foods in separate areas of the agricultural landscape. The origin of these shifts can be traced to transformational moments during the Huarás phase (400 BC–AD 200) when people gathered on Perolcoto's ceremonial mound to perform elaborate decommissioning rituals in Chavín spaces. In these moments, the people of Hualcayán not only destroyed and rebuilt sacred platforms: during these acts they displayed innovations in materials and food consumption practices by performing libation ceremonies with maize chicha beer and painted ceramics.

A second important focus of the excavations at Hualcayán has been uncovering ancient mortuary practices. Hualcayán has over one hundred tombs scattered across its Perolcoto, Panchucuchu and Ichic Tzacpa sectors. Our excavations in these tombs has revealed a great deal of well-preserved, though commingled, skeletal, textile, ceramic, lithic, and botanical remains, which a team of collaborators are using to reconstruct ancient funerary practices, diet, health, and violent interaction. We have focused particular analyses on the machay tombs built beneath boulders of the mountainside Ichic Tzacpa sector, the above-ground chullpa funerary structures built on the hilltop Panchucuchu sector, and semi-subterranean tombs intrusive into the ceremonial mound of the Perolcoto sector. These tombs were primarily built and used in Recuay times or later (AD 1–1450), though some may have been built earlier based on the occasional presence of Chavín and Huarás style ceramics.

We are only beginning to unravel the complex building history of domestic spaces in the hilltop Panchucuchu sector, where patio group residential units are densely arranged on top of platforms and within walled compounds. Ceramic remains indicate that the still-standing architecture in the sector was built during Recuay times and subsequently remodeled and reused by later inhabitants (AD 1–1450). Fancy, decorated ceramics found in these homes also suggest Recuay and later groups likely held small-scale feasts within their homes. Combined with the feasting evidence from other sectors, these data reveal how, during Recuay times, Hualcayán's social landscape was defined through a complex range of public and private ritual interactions focused on food consumption. Excavations also uncovered a small area of buried architecture with Chavín and Huarás cultural ceramic remains (900 BC–AD 200) indicating that the Recuay domestic complex was built over earlier houses that may date back to the community's founding. Future investigations will continue to explore this complex building history and the practices of domestic life for Hualcayán's inhabitants.

This collaborative research has also produced several research reports and numerous professional conference presentations by student and professional collaborators at the Society for American Archaeology and the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, among other academic venues. In addition, the following theses and dissertations have been completed through research at Hualcayán:

- Aguilar Aguilar, Roger Gustavo (2011). Presencia de la Tradición Arquitectónica Mito en el Montículo Principal del Sector A – Perolcoto, Complejo Arqueológico Hualcayán. (Practicas Pre-Profesionales de Bachiller), Universidad Nacional de Ancash Santiago Antúnez de Mayolo.

- Bria, Rebecca E. (2017). Ritual, Economy, and the Construction of Community at Ancient Hualcayán (Ancash, Peru). (PhD), Vanderbilt University.

- Cruzado Carranza, Elizabeth K. (2016). Characterizing the Mortuary Practices in Highland Ancash, Perú: Analysis of Funerary Contexts at Hualcayán. (MA), University of Memphis.

- Cuadros Benites, Rubith (2011). (Practicas Pre-Profesionales de Bachiller), Universidad Nacional de Ancash Santiago Antúnez de Mayolo.

- Gómez Támara, Evelyn (2015). Estructuras Funerarias del Horizonte Medio en el Sitio Arqueológico de Hualcayán, Callejón de Huaylas. (Practicas Pre-Profesionales de Bachiller), Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

- Granley, Elisabeth (2015). A Lithic Analysis of Food Preparation and Resource Distribution in Recuay Ritual Feasting Contexts at Hualcayán (Ancash, Peru). (B.A.), University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

- Grávalos, M. Elizabeth (2014). Conceptualizing community identity through ancient textiles: Technology and the uniformity of practice at Hualcayán, Peru. (M.S.), Purdue University (Ph.D. component in progress at the University of Illinois-Chicago).

- McAllister, Hannah (2015). Reconstructing a Recuay Feasting Event at Hualcayán, Peru Through Ceramic Analysis. (B.A.), University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

- Norgon, Kate (2013). Identifying mortuary ritual and ancestor veneration: A spatial analysis of the tombs at Hualcayán. (B.A.), University of Wisconsin-LaCross.

- Núñez Aparcana, Bryan A. (2012). Caracterización de la cerámica asociada a contextos Recuay en el Sector A-Perolcoto del Sitio Arqueológico de Hualcayan, Callejón de Huaylas, Ancash. (Practicas Pre-Profesionales de Bachiller), Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

- Pantel, Jessica (2011). Research on Patterns of Violence through Cranial Analysis in the Callejón de Huaylas Valley, Peru. (B.A. Honors Study), North Central College.

- Pink, Christine M. (2013). Striking out and digging in: A bioarchaeological perspective on the impacts of the Wari expansion on populations in the Peruvian central highlands. (Ph.D.), University of Tennessee-Knoxville.

- Salazar Mendoza, Nancy (2011). (Practicas Pre-Profesionales de Bachiller), Universidad Nacional de Ancash Santiago Antúnez de Mayolo.

- Sharp, Emily (2013). With Slings and Stones: Warrior Masculinity and the Bodily Consequences of Warfare in the North-Central Andes. (M.A.), Arizona State University (Ph.D. component in progress).

- Stokes, Joseph O. (2013). Musculoskeletal Interpretation of Labor Induced Stress on Ancient Andean Populations from Hualcayán (Ancash, Perú). (B.A.), Fort Lewis College.

- Tahua Espinoza, Sulma Karina (2011). Secuencia Ocupacional en la Operación 1 del Sector “A” - Perolcoto, del Sitio Arqueológico de Hualcayan-Huaylas. (Practicas Pre-Profesionales de Bachiller), Universidad Nacional de Ancash Santiago Antúnez de Mayolo.

- Witt, Rachel (2012). The Life Experience of the Mortuary Skeletal Sample from Machay 5: A Bioarchaeological Study of a Middle Horizon tomb from the north-central highlands, Peru. (B.A.), Vanderbilt University.

Translate This Page

All PIARA artwork, photos, and web and flyer designs are copyright © Rebecca E. Bria